I am sure by this stage of enjoying my blog (with me yet to provide any writings about me on the actual Silk Road) and by being generally learned people, you are, of course, familiar with what I mean by The Silk Road. However, I thought a wee post may be helpful to give you some background as where the term came from, the various routes, the goods travelling across it and what led to its eventual demise (other than for daft tourists suckered in by a Romantic idea of history) – particularly for those of you who have not done the recommended reading…

A hundred reasons clamour for your going. You go to touch on human identities, to people an empty map. You have notion that this-is the world’s heart. You go to encounter the protean shapes of faith. You go because you are still young and crave excitement the crunch of your boots in the dust; you go because you are old and need to understand something before it’s too late. nor go to see what will happen.

Yet to follow the Silk Road is to follow a ghost. It flows through behind it the the heart of Asia, but it has officially vanished, pattern of its restlessness: counterfeit borders, unmapped peoples. The road forks and wanders wherever you are. It is not a single way, but many: a web of choices.

Colin Thubron, Shadow of the Silk Road

The Name

No one who travelled the silk roads (more on the “s” below) would have called it or known it as such. The description of the Silk Road was first used by a German geologist in the late 19th century. Ferdinand von Richthoften (uncle of flying ace the “Red Baron”) coined the term (or the Seidenstraẞen he would have written it) as a way of trying to make sense of how the routes connected together and naming it after one of the key goods to traverse it, silk.

The Roads

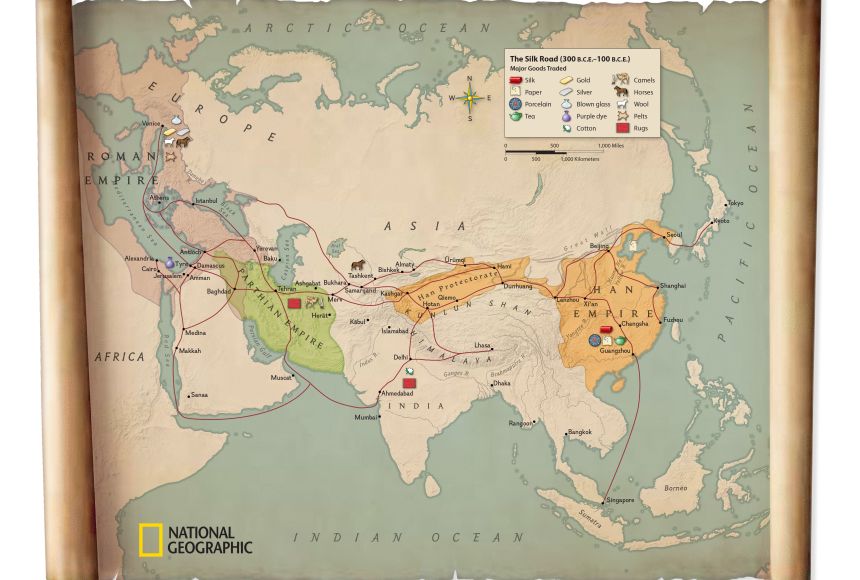

As the quote above alludes to, there isn’t even such thing as the Silk Road as it was never a single road. Rather, it was a sprawling web of routes covering vast distances with key common cities/stops along your average merchant’s journey.

There is also no definative agreement as to these actual routes either, however, its commonly understood to mean an overland journey starting in (modern day) Xi’an, China and ending in Istanbul, Turkey. You have various options in the middle, and I have chosen the Central Asian route.

The Goods

I suspect we can all guess that the Silk Road has something to do with the transportation of silk and yes, although many goods were transported East and West across the routes, it was the desire in the West for silk that really pushed goods along the route. Both for its strong and lustrous qualities, but apparently de riguer (intially) for those wanting a semi-seethrough toga!

The Chinese were not stupid – they had the monopoly on how to make silk, and they refused to share that knowledge. Apparently, anyone who told a foreigner the secret origins of silk was likely put to death (petit over-reaction perhaps?). It wasn’t until the 13th century that silk production started in Europe (once we’d figured it out so to say), and even then, this was considered to be a mere imitation of the far superior Eastern silk.

So what did the Chinese want in return? At the beginning (certainly according to the horse loving nations of the Stans) it was for the Central Asian horses, in particular breeds such as akhals which even based on my INCREDIBLY limited knowledge of horses, look very pretty:

Whilst we can agree that silk was the major product coming from China, there is a suggestion that from a Central Asian perspective, the Silk Road could more correctly be called the Paper Road. For hundreds of years, paper from Samarkand (where I shall be visiting later) was considered to be one of the most important and lucrative goods travelling east. With similarities to the silk story, it wasn’t until the 13th century that paper started to be produced in Europe. It was also the affordability of paper that enabled the cities of Central Asia as well as Cairo and Damascus to become centres of learning.

Also being traded was porcelin, lacquerware, tea and spices. In return, as well as those lovely horses, wool, glassware, and gold were heading east.

The Demise

Simply put, water. As sea routes became more navigable, with better ships, it was a much easier journey (and quicker) via sea than travelling overland. Sea routes also enabled European merchants to go direct to source rather than goods passing from merchant to merchant along the Silk Road.

Selected bibliography:

- The Lonely Planet Guide to Central Asia

- Shadow of the Silk Road and The Lost Heart of Asia both by Colin Thubron

- The Silk Roads – A New History of the World by Peter Frankopan (not yet finished)

- A Carpet Ride to Khiva by Christopher Aslan Alexander

- Sovietstan by Erika Fatland

- Travels by Marco Polo

- Land of Lost Borders by Kate Harris

- Stans by Me by Ged Gilmore

- Silk Road Adventure by Clare Burges Watson

- Silk Dreams, Troubled Road by Jonny Bealby