So, as I alluded to in my last post, yesterday we arrived in Jiayguan on the sleeper train. Well, “soft” sleeper is very much fanicer than my previous experiences on “hard” sleeper – 4 bunks rather than 6, water provided, lace tablecloth, even a western/sit down toilet. Oh, the luxury. I volunteered for the top bunk, and whilst I was less than elegant getting up (when people were watching), I was far more graceful coming down when no one was awake to see me!

Whilst we are still in Gansu province, we have definately entered more of a lunar landscape with flat biege land up to to a mountain and then suddenly the beige turns into green as the land has been irrigated and single story houses/farms start to pop up.

On arrival we were met by our new local guide Amy (who is proving to be excellent) and we were able to check in early to the hotel for much needed showers after a rather warm night on the train…

Jiayguan marks the end of the Great Wall, the Western gateway which seperates Imperial China from the land of nothing/hoards/the horreurs of foreigners with their strange ways and customs… We are threading through the Hexi corridor between the snowcapped Qillian mountains to the South and the Black mountains to the north. It is today a huge industrial area – for example, the metal that made the Birds Nest at the Beijing Olympics was produced here. It has a population of a mere 200,000, possibly because in the summer, it gets incredibly hot.

A quick lunch stop where along with our first bread of this trip (a cicular naan bread topped with a delicious beef stew) I also got some interior design inspiration:

That afternoon our first stop was the “Overhanding Great Wall” built on the eastern slope of the Black mountain. Although it has the recognisable undulating look as the western parts of the Great Wall, whilst that is made of bricks, as we are effectively in the desert, here they use clay, mud and straw. This part of the wall dates back to the Ming dynasty (1539AD), but much of what is here was rebuilt in the 1970s. It was built to strengthen the defensive capability of this area and was intended to be a “hidden” wall as it is not visible to anyone coming from the west or east and would only be faced with it onced they had scaled the mountain. Originally, it would have been 1.5km long, but only 750m has been rebuilt.

I decided it being around 30 degrees and sunny that I would just walk part of the way up and then turn around and come back. That was my plan anyway, but I got overconfident perhaps, and as I kept turning a corner, I wanted to keep going. For context, it’s an uphil climb (a mix of steps and slope) 0f 231m tilting at a 45-degree angle. A rather sweaty but very proud me did indeed make it to the top! At the bottom, I rewarded myself with a tepid tea (the Chinese do not believe in chilled drinks ) and a sit.

We then headed to see the Wei-Jin tombs, which date back to 220-420AD. Now, in my mind, these were going to be a selection of tombs, but in reality, it’s a large expanse of gravely space with the odd mound. In order to protect the tomb, only 1 is opened to the public, and actually only 12 have been excavated – oh, and no photos inside. The tomb where visitors are permitted, belonged to a wealthy couple, and the painted bricks depict local life (it is from this area that the postman brick in the Gansu museum comes from). From my perspective, they could almost be modern cartoons, but perhaps this is the earliest form of this style.

After another delightful meal (where I remembered to take photos) and rather aggressive game of mahjong (Amy felt very strongly that she should win), I tried and failed to purchase an esim (turns out neither my phone or tablet allow a dual sim which is very anoying and I am thinking Samsung may be about to lose my loyalty!), I then excelled myself at Monopoly Deal before heading off to bed.

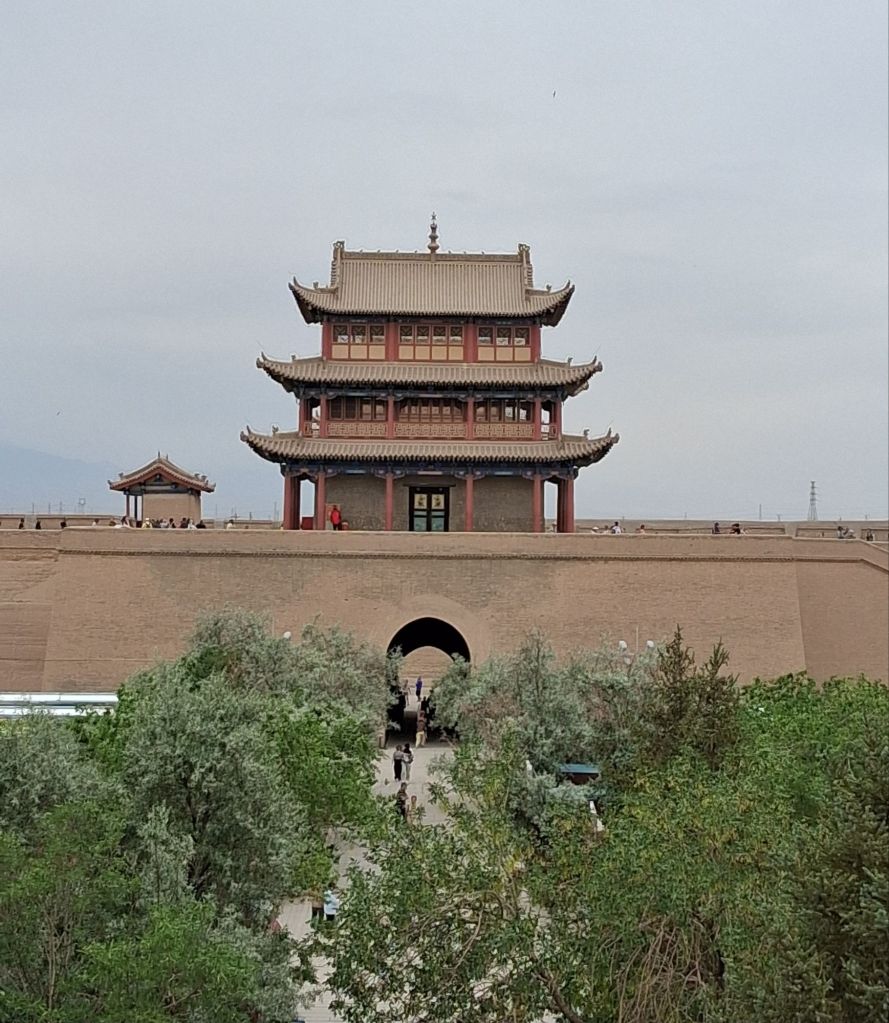

The reason most people come to Jiayguan is to visit the Jiayguan Fortress. This fortress guarded the far northwesterm area of China and was constructed during the Ming dynasty (started in 1372 and taking 168 years). It was also a key waypoint on the Silk Road as the first entry point into China, as well as the last vesitages of civilastion from a Chinese perspective. However, and excitingly for the foreign tourist, Jiayguan Pass is still the most intact (and take that to read minimally reconstructed) ancient military building.

For me, this is going to go down as perhaps the best (so far) example of Chinese tourism. I had imagined approaching a dusty, semi-ruined fort and casually walking around it. This is not how modern China does things. You arrive into a very Disney-esq queuing area, board an electric car (4 to a row – no exceptions) camouflaged as a camel, drive through a green parklike oasis, and are dropped off at the main entrance (another queuing area), walk around a lake lined with vendors selling various snacks and then approach the fort. On arrival into the area right infront of the fort, there was a celebration of culture and world heritage going on, which included a stage and a pretty impressive sound system (go loud or go home). Then, fnially, you can enter the fortress – National Trust it is not…

Anyway, let us return to the fort itself. As you can see below the fort is made up of an inner courtyard, trap or net courtywards to impeede invading armies and an outer wall with a watchtower ever 2.5km (fortresses were built every 50km along the wall).

You will see that we again have the sandy walls of this region – these were made:

- Take soil from the Gobi Desert and filter out larger stones.

- Roast this soil in a wok to dry it out and kill any grass seeds (a sprouting wall is not a strong wall).

- Mix with mud and sticky rice water.

- Pack this down into a strong cmpounded wall.

- Repeat.

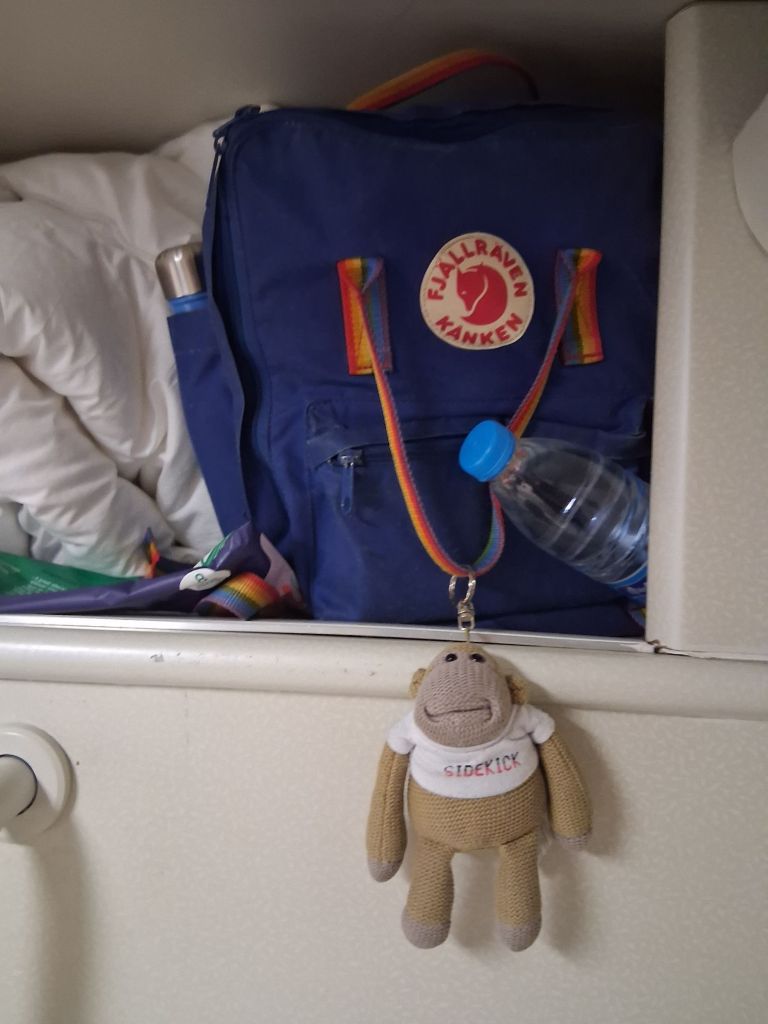

On the top of the wall, there is a point labelled “best photo spot,” and I, emulating Xi Xi Ping, had my photo taken looking symbolically out across my dominion. I took a less majestic photo of the monkey..

You exit through the Western gate, this is up a steep slope which runs down into the gate and then you are faced with an almost immediate wall – this was designed aginst the horse ridng mongols who would have sped down into the gate and then be force to make an almost impossible sharp turn. Ingeniuos. Today, on exiting the gate, you have some rather bored looking camels, but an expanse view out into (from a Chinese perspective) nowhere.

I am writing this on the 5 hour drive from Jiayguan to Dunhang – the scenery is not changing and the road could be smoother (I expect more from Chinese roads) and most of the group seem to be napping off lunch. Perhaps its time for me to get on with my cross stitch (I do like to have a little “work” with me) and stare into the nothingness…

The answers to yesterday’s quiz question re: Yemen, Seychelles Chili, Fiji and Lichtenstein. Today, rather than geography we were guessing the numbers of particular animals in China (possibly ispired by the cooking depictions in the tombs). So: what is the ratio of sheep to people in China? Answer in the next post.

Leave a comment